light-years: ly009

Caterina Barbieri and Bendik Giske - At Source

Order At Source

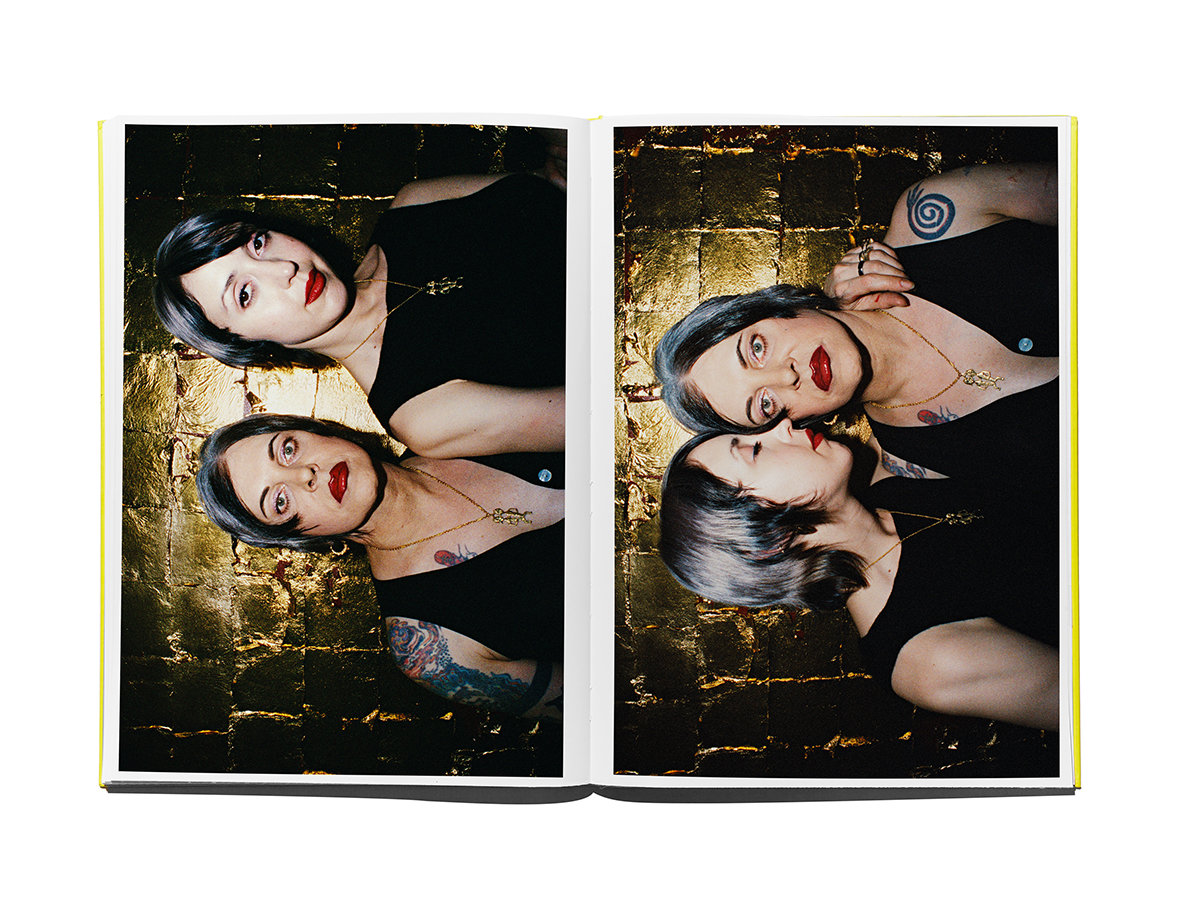

Caterina Barbieri & Bendik Giske's At Source resounds music as wellspring, that which is essential and unknowable, and yet utterly primary. It finds two acclaimed composer-musicians building a world together in self-contained collaboration between analogue synthesis and an extended approach to the saxophone that conjures its own universe of sound. It is at once intimate and cosmic, drawing on the challenges and possibilities of their artistic exchange, tearing down technique to access all the expansive possibilities of their sonic meeting point.

At Source is a document of the world of sound to be conjured when two artists strive for something together, discovering the expansions and limitations of performance by bodies and machines. It is not an exercise in assimilation, but in productive exchange and creative confrontation. It does not draw on outside energies or influences, but grapples with what there is to find in their respective playing. "It also reflects how natural the collaboration was," says Barbieri, "a meeting at the source which was spontaneous, graceful and natural".

Barbieri and Giske first met and were enthralled by one another's performances at Kunsthaus Glarus in 2019, a meeting that spurred conversations on the power of transitions as a compositional force. Giske later contributed a rework of Fantas for Fantas Variations (Editions Mego, 2021), an ambitious undertaking to rescore Barbieri’s work for his saxophone and voice, a challenge Giske had started undertaking two years prior as an ongoing practice of transcription. “The request came as a proof of aligned ideas”, says Giske.

Their new collaborative project then started during an artistic residency in Milan’s ICA in 2021, by invitation of swiss artist and curator Jan Vorisek, as the world was emerging from lockdown. This meeting, and the preceding closure of sites for cultural exchange, made their work together 'feel like springtime' says Barbieri. Giske, who was on the brink of releasing his sophomore album, Cracks, then joined Barbieri's light-years tour, which functioned as an inaugural incarnation of her newborn label and platform through a series of multi-artist curated shows with appearances of Lyra Pramuk, Nkisi, MFO, among other artists.

Through the tour, they continued to develop material live, and this record, laid down in the studio, is true to that ever-evolving process of creation, where live feedback stays essential to the vitality of this collaborative effort. The tracks are each named with two evocative words that contain the two poles of their sound. Theirs is both abstract and cosmic, in the synth as machine undermined by Barbieri's naturalistic playing, and in Giske's continuous exploration of the symbiosis between his instrument, voice, and body. These binaries, of body and machine, posed various challenges, notably in how the stepped patterns Barbieri uses were near-impossible to translate for Giske's body to perform, and other times where mathematical resolutions were needed to sync their playing. Explains Giske: "It forced me to go to the core of what I am and what I have to offer”. Barbieri says that it "explores the liminality between the machine and the human, and the vulnerability in this process".

On 'Intuition, Nimbus', the first track to be written, Giske's playing flutters and rises on Barbieri's synth, like a flock of birds lifted skywards on thermal columns, with clouds of pulsing tones fanning avian wings. 'Alignment, Orbit' settles into a steady torque, Giske's gentle percussions syncing with shifting loops, steadily building energy and conjuring solidity from breath and resistance. The extended 'Impatience, Magma' stretches glowing and languorous, honing in on and picking up a synth melody with whetted edge that cuts through the firmament, populating a broad cosmos of extended tones and replicating patterns in a piece that calls to mind Laurie Spiegel's extended works, and steps into transcendent duet with Giske's saxophone at its most keening and spiritual in tone and movement. 'Persistence, Buds' unfurls gracefully in sensuous sympatico, as saxophone caresses Barbieri's slowly twirling progressions, a tactile and meditative closer.

At Source is testament to two divergent practices finding a whole cosmos in which to convene; music is crystalised and made utterly enveloping through the focused and critical work of two musicians working at their peak. The versions here are, temptingly, "just one of many versions" of this abundant source material Giske explains. Like the best collaborations, At Source is more than the sum of its parts – bringing more to the feast than the simple combination of two musicians, promising versions upon versions of the exquisite material captured here.

CREDITS

Caterina Barbieri and Bendik Giske - At Source

Order At Source

Caterina Barbieri & Bendik Giske's At Source resounds music as wellspring, that which is essential and unknowable, and yet utterly primary. It finds two acclaimed composer-musicians building a world together in self-contained collaboration between analogue synthesis and an extended approach to the saxophone that conjures its own universe of sound. It is at once intimate and cosmic, drawing on the challenges and possibilities of their artistic exchange, tearing down technique to access all the expansive possibilities of their sonic meeting point.

At Source is a document of the world of sound to be conjured when two artists strive for something together, discovering the expansions and limitations of performance by bodies and machines. It is not an exercise in assimilation, but in productive exchange and creative confrontation. It does not draw on outside energies or influences, but grapples with what there is to find in their respective playing. "It also reflects how natural the collaboration was," says Barbieri, "a meeting at the source which was spontaneous, graceful and natural".

Barbieri and Giske first met and were enthralled by one another's performances at Kunsthaus Glarus in 2019, a meeting that spurred conversations on the power of transitions as a compositional force. Giske later contributed a rework of Fantas for Fantas Variations (Editions Mego, 2021), an ambitious undertaking to rescore Barbieri’s work for his saxophone and voice, a challenge Giske had started undertaking two years prior as an ongoing practice of transcription. “The request came as a proof of aligned ideas”, says Giske.

Their new collaborative project then started during an artistic residency in Milan’s ICA in 2021, by invitation of swiss artist and curator Jan Vorisek, as the world was emerging from lockdown. This meeting, and the preceding closure of sites for cultural exchange, made their work together 'feel like springtime' says Barbieri. Giske, who was on the brink of releasing his sophomore album, Cracks, then joined Barbieri's light-years tour, which functioned as an inaugural incarnation of her newborn label and platform through a series of multi-artist curated shows with appearances of Lyra Pramuk, Nkisi, MFO, among other artists.

Through the tour, they continued to develop material live, and this record, laid down in the studio, is true to that ever-evolving process of creation, where live feedback stays essential to the vitality of this collaborative effort. The tracks are each named with two evocative words that contain the two poles of their sound. Theirs is both abstract and cosmic, in the synth as machine undermined by Barbieri's naturalistic playing, and in Giske's continuous exploration of the symbiosis between his instrument, voice, and body. These binaries, of body and machine, posed various challenges, notably in how the stepped patterns Barbieri uses were near-impossible to translate for Giske's body to perform, and other times where mathematical resolutions were needed to sync their playing. Explains Giske: "It forced me to go to the core of what I am and what I have to offer”. Barbieri says that it "explores the liminality between the machine and the human, and the vulnerability in this process".

On 'Intuition, Nimbus', the first track to be written, Giske's playing flutters and rises on Barbieri's synth, like a flock of birds lifted skywards on thermal columns, with clouds of pulsing tones fanning avian wings. 'Alignment, Orbit' settles into a steady torque, Giske's gentle percussions syncing with shifting loops, steadily building energy and conjuring solidity from breath and resistance. The extended 'Impatience, Magma' stretches glowing and languorous, honing in on and picking up a synth melody with whetted edge that cuts through the firmament, populating a broad cosmos of extended tones and replicating patterns in a piece that calls to mind Laurie Spiegel's extended works, and steps into transcendent duet with Giske's saxophone at its most keening and spiritual in tone and movement. 'Persistence, Buds' unfurls gracefully in sensuous sympatico, as saxophone caresses Barbieri's slowly twirling progressions, a tactile and meditative closer.

At Source is testament to two divergent practices finding a whole cosmos in which to convene; music is crystalised and made utterly enveloping through the focused and critical work of two musicians working at their peak. The versions here are, temptingly, "just one of many versions" of this abundant source material Giske explains. Like the best collaborations, At Source is more than the sum of its parts – bringing more to the feast than the simple combination of two musicians, promising versions upon versions of the exquisite material captured here.

CREDITS

light-years: ly008

Georg Gatsas - The Process

Order The Process

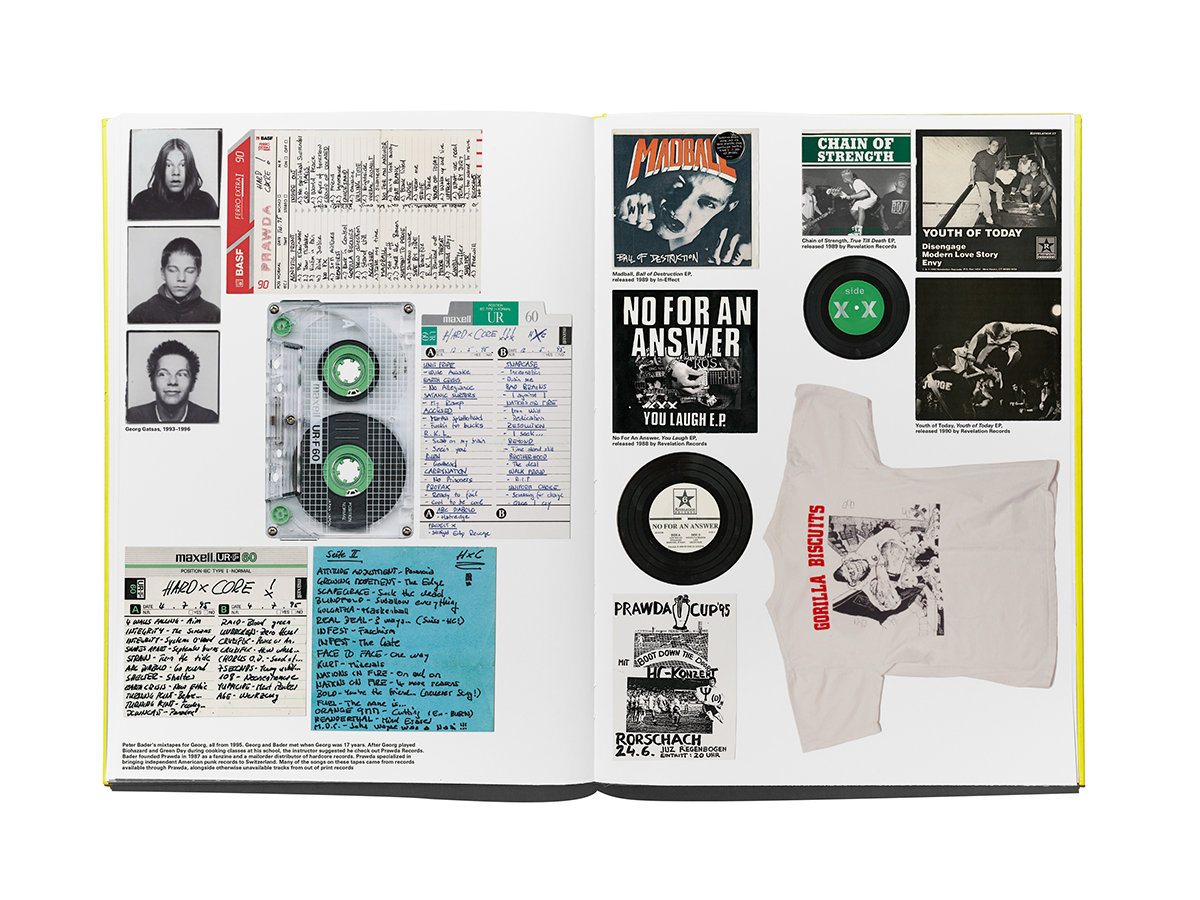

The Process is the first book from light-years, the independent music label founded by Caterina Barbieri in 2021. It brings together Swiss artist Georg Gatsas’s early photographic work, documenting New York’s underground music and art scenes between 2002 and 2007. Alongside the large format reproductions of photographs, the book presents a vast collection of record covers, garments, correspondence, and ephemera from Georg’s personal archive.

Georg Gatsas (b. 1978, Switzerland) is an artist who uses still and moving photography to map the intersections between creativity, location, memory, and focus. A steadfast participant in DIY and underground creative communities, he has spent his life unveiling the connections that bind artists across genre, generation, and identity. Solo exhibitions of his work have been mounted by Kunsthalle St. Gallen, Switzerland; The Swiss Institute, New York; and JUBG, Cologne. His work has appeared in The Wire, zweikommasieben, and ANP Quarterly, and monographs dedicated to Georg’s photography have been published by Nieves (Switzerland) and Loose Joints (France and UK).

Spanning 2002 - 2007, The Process was Georg’s first major series, documenting five years of life in New York City. It’s an alienating span of time, bookended by September 11 on one side and the emergence of the smartphone on the other. The terrified, reactionary America of these five years craved comfort and safety, but a spiky, risky underground coalesced in that creative dead zone. In Georg’s words, “There was a sense of most of the world not understanding. And this is an opportunity.” The predominant culture’s patriotism and assuredness left a lot of unsupervised space for individuals interested in addressing fear and danger. It sometimes felt as if entire city blocks had been abandoned, the remnants corrupted and rebuilt by bands and artists, by concerts and exhibitions with small, dedicated audiences. This was the terrain of The Process.

Georg sought out the people wandering this terrain, and made portrait of them: Genesis P-Orridge, Black Dice, Antipop Consortium, Kembra Pfahler, Ira Cohen and Stephonik Youth. These are not artists bound together by generation or gesture, rather they are connected through their dedication and intention. They share a sense of refusal, and an ability to see the opportunity in not being understood, in not being recuperable. Everyone in these photos is on edge, tense and tightly-wound. Their faces display the same resistance that you hear in their songs and read in their words. Georg matched their focus and ruthlessness in his photographs. The direct eye contact is consistent. The camera’s unobstructed harshness is consistent. Even the non-portrait photos—a cat-filled alley or an empty parking lot—ask the same questions about belonging, about looking away. About the potential of a broken umbrella, or the everyday ad hoc approaches to evading systemic annihilation.

The Process is the first book issued by light-years, the independent label founded by Caterina Barbieri in 2021. Light-years is known best for densely-crafted, labyrinthine compositions, and The Process is no exception. Alongside the large format reproductions of photographs, the book presents a vast collection of record covers, garments, correspondence, and ephemera from Georg’s personal archive. Alternating between Georg’s portraits, these archival spreads are initially obscured from view through the use of an antiquated printing technique which leaves the top edge of the book uncut. The folded gathering at the top edge of each page must be sliced with a sharp edge to reveal the book in its entirety, a practice entirely familiar to 19th century readers, but nearly forgotten today. The poet Stéphane Mallarmé rejoiced in the process of separating pages with a blade, noting the action was the only way to introduce movement to a book. In his 1895 essay The Book: A Spiritual Instrument, Mallarmé wrote that the uncut foldings “invite the kind of sacrifice that made the red edges of ancient tomes bleed; I mean that they invite the paper-knife, which stakes our claims to possession of the book.”

This design ultimately makes clear the intent of The Process, and of Georg’s practice as a whole. Reflecting on this incipient body of work decades after its completion, Georg observed, “You can see I just started.” It sounds like an admission that he’d only just begun using the camera in those years, but it can be reframed as an affirmation, an understanding that he jumped in and used the camera without hesitation. That he didn’t fret, didn’t strategize. That movement must be introduced, even blood, but this dedication and resistance is within reach for anyone with the will to reach out for it, to stake the claim.

(Ethan Swan)

CREDITS

Georg Gatsas - The Process

Order The Process

The Process is the first book from light-years, the independent music label founded by Caterina Barbieri in 2021. It brings together Swiss artist Georg Gatsas’s early photographic work, documenting New York’s underground music and art scenes between 2002 and 2007. Alongside the large format reproductions of photographs, the book presents a vast collection of record covers, garments, correspondence, and ephemera from Georg’s personal archive.

Georg Gatsas (b. 1978, Switzerland) is an artist who uses still and moving photography to map the intersections between creativity, location, memory, and focus. A steadfast participant in DIY and underground creative communities, he has spent his life unveiling the connections that bind artists across genre, generation, and identity. Solo exhibitions of his work have been mounted by Kunsthalle St. Gallen, Switzerland; The Swiss Institute, New York; and JUBG, Cologne. His work has appeared in The Wire, zweikommasieben, and ANP Quarterly, and monographs dedicated to Georg’s photography have been published by Nieves (Switzerland) and Loose Joints (France and UK).

Spanning 2002 - 2007, The Process was Georg’s first major series, documenting five years of life in New York City. It’s an alienating span of time, bookended by September 11 on one side and the emergence of the smartphone on the other. The terrified, reactionary America of these five years craved comfort and safety, but a spiky, risky underground coalesced in that creative dead zone. In Georg’s words, “There was a sense of most of the world not understanding. And this is an opportunity.” The predominant culture’s patriotism and assuredness left a lot of unsupervised space for individuals interested in addressing fear and danger. It sometimes felt as if entire city blocks had been abandoned, the remnants corrupted and rebuilt by bands and artists, by concerts and exhibitions with small, dedicated audiences. This was the terrain of The Process.

Georg sought out the people wandering this terrain, and made portrait of them: Genesis P-Orridge, Black Dice, Antipop Consortium, Kembra Pfahler, Ira Cohen and Stephonik Youth. These are not artists bound together by generation or gesture, rather they are connected through their dedication and intention. They share a sense of refusal, and an ability to see the opportunity in not being understood, in not being recuperable. Everyone in these photos is on edge, tense and tightly-wound. Their faces display the same resistance that you hear in their songs and read in their words. Georg matched their focus and ruthlessness in his photographs. The direct eye contact is consistent. The camera’s unobstructed harshness is consistent. Even the non-portrait photos—a cat-filled alley or an empty parking lot—ask the same questions about belonging, about looking away. About the potential of a broken umbrella, or the everyday ad hoc approaches to evading systemic annihilation.

The Process is the first book issued by light-years, the independent label founded by Caterina Barbieri in 2021. Light-years is known best for densely-crafted, labyrinthine compositions, and The Process is no exception. Alongside the large format reproductions of photographs, the book presents a vast collection of record covers, garments, correspondence, and ephemera from Georg’s personal archive. Alternating between Georg’s portraits, these archival spreads are initially obscured from view through the use of an antiquated printing technique which leaves the top edge of the book uncut. The folded gathering at the top edge of each page must be sliced with a sharp edge to reveal the book in its entirety, a practice entirely familiar to 19th century readers, but nearly forgotten today. The poet Stéphane Mallarmé rejoiced in the process of separating pages with a blade, noting the action was the only way to introduce movement to a book. In his 1895 essay The Book: A Spiritual Instrument, Mallarmé wrote that the uncut foldings “invite the kind of sacrifice that made the red edges of ancient tomes bleed; I mean that they invite the paper-knife, which stakes our claims to possession of the book.”

This design ultimately makes clear the intent of The Process, and of Georg’s practice as a whole. Reflecting on this incipient body of work decades after its completion, Georg observed, “You can see I just started.” It sounds like an admission that he’d only just begun using the camera in those years, but it can be reframed as an affirmation, an understanding that he jumped in and used the camera without hesitation. That he didn’t fret, didn’t strategize. That movement must be introduced, even blood, but this dedication and resistance is within reach for anyone with the will to reach out for it, to stake the claim.

(Ethan Swan)

CREDITS

light-years: ly007

Walter Zanetti - Cantos Yoruba de Cuba

Order Cantos Yoruba de Cuba

Santería draws heavily on music for its ceremonies. This Afro-Cuban syncretic religion, sometimes called La Regla de Ocha, saw the Orisha deities of the West African Yoruba peoples codified with Catholic saints. Yoruba practitioners, brought by force to the West, continued to worship their gods under the nose of those who sought to dehumanize them by adopting their spiritual language.

The chants that became Santería’s prayers were often accompanied by the beat of the batá drum. This heartbeat runs through every invocation, through every sacred song. In the same way that the shuffling chains on the feet of enslaved African peoples dancing defiantly in Colombia birthed the distinctive rhythm of cumbia, syncretism has been present in music as much as it has in religion. It has always been about challenging the odds, about creation, creativity, and heart.

This is why Italian musician Walter Zanetti’s guitar pierces straight to the soul on his Cantos Yoruba de Cuba. The guitarist’s latest album, light-years’ seventh release and its first outside the realm of electronic music, draws directly from the work of Cuban guitarist-composers José Angel Navarro and the late Hector Angulo. The 15-track album of new recordings from Zanetti brings together six original compositions by Navarro dictated to the Italian guitarist on a month-long trip to Cuba and reinterpretations of Angulo’s nine original Cantos Yoruba de Cuba, which give the record its name.

“I have always had a strong attraction for rhythm and polyrhythm. These aspects presented themselves to me in a surprising way when listening to Navarro's music, from which I perceived an extraordinary expressive force linked not only to the pure invention of the author but also to a centuries-old musical tradition with strong African roots,” says Zanetti.

A frequent visitor to Cuba, Zanetti first connected with Navarro’s work when he discovered the latter’s first album Miel, a work that itself draws from Yoruba chants, as well as the music of Afro-Cuban religions like Arará and Abakuá. Through mutual colleague Jorge Luis Zamora, the two were put in touch as Zanetti embarked on a visit to Cuba. Once on the island, the pair embarked on a collaboration that took Zanetti to Navarro’s hometown of Güines. Spending time with Navarro in this small town to the south of Havana, a space alive with the sound of authentic batá drums and Santería rites, Zanetti was able to immerse himself and observe. He learned directly from ceremonial percussionists and from Navarro himself, who had invented a complex technique that recreates the batá drum’s polyrhythms, timbre, and variations on guitar while maintaining a melodic line.

“I knew that composing with polyrhythms and polyphony at the same time would be a challenge as it required writing music in a new way to differentiate what notes belonged to the rhythm and what belonged to the melody,” says José Angel Navarro on the music he later taught Zanetti. “Very little has been written about the roots of this music. The ceremonies are secret, passed along through word-of-mouth. There are a lot of modifications on the songs depending on what village or region they are played in. I was lucky to be born in Güines, which was central to sugarcane farming in Cuba. There’s a large concentration of African-descended peoples who brought their traditions and adapted them —what is known as ‘syncretism’. As I perfected my technique of bringing these sacred polyrhythms to the guitar, the songs were approved by priests who recognized the songs of each Orisha and helped me tweak my versions as close as possible to the original songs. As I taught Walter [Zanetti], I told him to put any classical technique to the side.”

The result, after months of learning by imitation and supplementing the lessons with close-listens of key Cuban singer of Santería chants Lazaro Ros, is a stunning record that builds upon the work of Cuban master guitarists, vocalists, and priests of Santería’s rites and imbues them with new life. Kicked off with a lively 11-minute rendition of “Guaguanco, Conga, Colombia” from Navarro’s Miel, the record moves through the discographies of Navarro and Angulo, using the guitar to channel the high and low registers of batá drumming. Zanetti’s guitar invokes tender spiritual depths with soft strumming (“Borotiti”), somber plucking that almost emulates an angelic harp (“Ibu”), and lively, energetic playing that vibrates with unmistakable warmth (“Sumu Gaga”). Zanetti’s take on these sacred Afro-Cuban polyrhythms was recorded at an 11th-century Benedictine monastery in Ganna, a small town within the north Italian province of Varese.. While preparing for the undertaking, he offered a small prayer to Ochún, the Orisha of love and fertility.

“When you enter the ancient monasteries of the Romanesque era, the echoes of Gregorian chant resurface and you perceive the roots of a profound spirituality that dates back to the dawn of Christianity. In the West, however, the profound meaning of the function of music within it has lost its original meaning: the spiritual dimension now has more of an individual than collective value. The music of Santeria —passed down orally— has a function linked to a complex context where music, singing, and dance contribute to reaching an emotional state where participants can get closer to a spiritual dimension. This centuries-old tradition is still very much alive in the Cuban people. To find myself in a monastery playing music inspired by the traditions of Cuban Santeria unites artistic expressions that address the transcendent.”

The power of Cantos Yoruba de Cuba reverberating off the walls of a monastery — Africa reaching The Caribbean and making its way to an Italian monastery — cannot be understated. Zanetti’s ability to translate the batá drum and the teachings of Navarro and Angulo into guitar, to bring forth these hidden teachings to a broader audience, is in and of itself an act of syncretism, a collision of intention and location that combines Western musical teachings and brings them crashing into contact with Cuba’s esoteric traditions to create something truly transcendental.

(E.R. Pulgar, Cariño)

CREDITS

Walter Zanetti - Cantos Yoruba de Cuba

Order Cantos Yoruba de Cuba

Santería draws heavily on music for its ceremonies. This Afro-Cuban syncretic religion, sometimes called La Regla de Ocha, saw the Orisha deities of the West African Yoruba peoples codified with Catholic saints. Yoruba practitioners, brought by force to the West, continued to worship their gods under the nose of those who sought to dehumanize them by adopting their spiritual language.

The chants that became Santería’s prayers were often accompanied by the beat of the batá drum. This heartbeat runs through every invocation, through every sacred song. In the same way that the shuffling chains on the feet of enslaved African peoples dancing defiantly in Colombia birthed the distinctive rhythm of cumbia, syncretism has been present in music as much as it has in religion. It has always been about challenging the odds, about creation, creativity, and heart.

This is why Italian musician Walter Zanetti’s guitar pierces straight to the soul on his Cantos Yoruba de Cuba. The guitarist’s latest album, light-years’ seventh release and its first outside the realm of electronic music, draws directly from the work of Cuban guitarist-composers José Angel Navarro and the late Hector Angulo. The 15-track album of new recordings from Zanetti brings together six original compositions by Navarro dictated to the Italian guitarist on a month-long trip to Cuba and reinterpretations of Angulo’s nine original Cantos Yoruba de Cuba, which give the record its name.

“I have always had a strong attraction for rhythm and polyrhythm. These aspects presented themselves to me in a surprising way when listening to Navarro's music, from which I perceived an extraordinary expressive force linked not only to the pure invention of the author but also to a centuries-old musical tradition with strong African roots,” says Zanetti.

A frequent visitor to Cuba, Zanetti first connected with Navarro’s work when he discovered the latter’s first album Miel, a work that itself draws from Yoruba chants, as well as the music of Afro-Cuban religions like Arará and Abakuá. Through mutual colleague Jorge Luis Zamora, the two were put in touch as Zanetti embarked on a visit to Cuba. Once on the island, the pair embarked on a collaboration that took Zanetti to Navarro’s hometown of Güines. Spending time with Navarro in this small town to the south of Havana, a space alive with the sound of authentic batá drums and Santería rites, Zanetti was able to immerse himself and observe. He learned directly from ceremonial percussionists and from Navarro himself, who had invented a complex technique that recreates the batá drum’s polyrhythms, timbre, and variations on guitar while maintaining a melodic line.

“I knew that composing with polyrhythms and polyphony at the same time would be a challenge as it required writing music in a new way to differentiate what notes belonged to the rhythm and what belonged to the melody,” says José Angel Navarro on the music he later taught Zanetti. “Very little has been written about the roots of this music. The ceremonies are secret, passed along through word-of-mouth. There are a lot of modifications on the songs depending on what village or region they are played in. I was lucky to be born in Güines, which was central to sugarcane farming in Cuba. There’s a large concentration of African-descended peoples who brought their traditions and adapted them —what is known as ‘syncretism’. As I perfected my technique of bringing these sacred polyrhythms to the guitar, the songs were approved by priests who recognized the songs of each Orisha and helped me tweak my versions as close as possible to the original songs. As I taught Walter [Zanetti], I told him to put any classical technique to the side.”

The result, after months of learning by imitation and supplementing the lessons with close-listens of key Cuban singer of Santería chants Lazaro Ros, is a stunning record that builds upon the work of Cuban master guitarists, vocalists, and priests of Santería’s rites and imbues them with new life. Kicked off with a lively 11-minute rendition of “Guaguanco, Conga, Colombia” from Navarro’s Miel, the record moves through the discographies of Navarro and Angulo, using the guitar to channel the high and low registers of batá drumming. Zanetti’s guitar invokes tender spiritual depths with soft strumming (“Borotiti”), somber plucking that almost emulates an angelic harp (“Ibu”), and lively, energetic playing that vibrates with unmistakable warmth (“Sumu Gaga”). Zanetti’s take on these sacred Afro-Cuban polyrhythms was recorded at an 11th-century Benedictine monastery in Ganna, a small town within the north Italian province of Varese.. While preparing for the undertaking, he offered a small prayer to Ochún, the Orisha of love and fertility.

“When you enter the ancient monasteries of the Romanesque era, the echoes of Gregorian chant resurface and you perceive the roots of a profound spirituality that dates back to the dawn of Christianity. In the West, however, the profound meaning of the function of music within it has lost its original meaning: the spiritual dimension now has more of an individual than collective value. The music of Santeria —passed down orally— has a function linked to a complex context where music, singing, and dance contribute to reaching an emotional state where participants can get closer to a spiritual dimension. This centuries-old tradition is still very much alive in the Cuban people. To find myself in a monastery playing music inspired by the traditions of Cuban Santeria unites artistic expressions that address the transcendent.”

The power of Cantos Yoruba de Cuba reverberating off the walls of a monastery — Africa reaching The Caribbean and making its way to an Italian monastery — cannot be understated. Zanetti’s ability to translate the batá drum and the teachings of Navarro and Angulo into guitar, to bring forth these hidden teachings to a broader audience, is in and of itself an act of syncretism, a collision of intention and location that combines Western musical teachings and brings them crashing into contact with Cuba’s esoteric traditions to create something truly transcendental.

(E.R. Pulgar, Cariño)

CREDITS

light-years: ly006

Ludwig Wandinger - Is Peace Wild?

Order Is Peace Wild?

An album of hypnagogic nocturnes that relentlessly searches for a sense of calm in the great unknown, 'Is Peace Wild?' is German producer, drummer and visual artist Ludwig Wandinger's upcoming release on light-years. He dreamt it up while unpacking the breakdown of a long relationship, working in hotel rooms during the downtime between a series of chaotic live shows. To help empty his mind, Wandinger developed a suite of soulful reflections that prioritize harmony over rhythm and clarity over trivial complexity - music that confronts the eternal duality of romance and tragedy. Almost beatless and consistently sublime, 'Is Peace Wild?' is punctuated by hypnotic lyrical contributions from multi-disciplinary artist, poet and activist Yves B. Golden and producer and vocalist Evita Manji, both of whom bless the album with indispensable friendship and familiarity. "It's almost as if they were telling me a good night story," says Wandinger.

With a series of albums and EPs under his belt already, Wandinger is a tireless solo artist and a prolific collaborator. He's released material for Orange Milk, Gin&Platonic, Creamcake, 3XL, and he worked alongside artists such as Evita Manji, Sara Persico, Grischa Lichtenberger and Brodinski. 'Is Peace Wild?' though emerges as Wandinger’s most personal work to date. The title track opens the album, and Golden's voice breathes softly over Wandinger's warm, lulling arpeggios. "Balloons and birds delight in the flow of air between rooms," she murmurs, floating her surreal phrases in a tranquil pool of pitch-skewed pads and chiming, music box synths. But this airiness doesn't last long: on the noisy, sombre 'Vien', Wandinger interrupts his elegiac, organ-like synths with metallic crashes and distorted, rasping bass, weaving twinkling, pensive notes into the spaces in-between. The oscillation between darkness and light is remarkably even-handed, capturing the aching sense of longing - or "Sehnsucht" - that's at the core of German Romanticism. And it's even more evident on 'Xhausted Form', one of the album's heaviest tracks. Unfolding initially with affecting, sacred chords, the serenity is challenged by eerie, dissonant crunches and unsettling feedback shrieks, yet the spark of romance, in all of its intricacy, never diminishes.

Meanwhile, the album's illusory qualities are fully dilated on 'Fire'. Manji's hypnotic freestyle was recorded in a single take as they were lying in bed on the verge of falling asleep, and provides a quiescent counterpoint to Wandinger's muted trance vibrations. "The world is on fire drowning in its own fluids," they slur into the abyss, vocalizing playfully while Wandinger freezes the sentiment in vanishing 4/4 thuds and dissociated processes. This makes the baroque 'Overlife' and the noisy 'Eternal Image' all the more dynamic. On the latter, Wandinger creates a noisy, apocalyptic atmosphere for Golden's sardonic words, cooling his euphoric synths with hissing white noise and burnished cybernetic textures. "They are afraid of loud noises," Golden mouthes. "Bodies like mine are made for turbulence."

Open-ended and tangled with emotional paradoxes, 'Is Peace Wild?' can be interpreted in many different ways. Wandinger's own serenity is personal, but laying himself bare, he provides listeners with a cracked mirror to consider their unique patchwork of conundrums.

CREDITS

Ludwig Wandinger - Is Peace Wild?

Order Is Peace Wild?

An album of hypnagogic nocturnes that relentlessly searches for a sense of calm in the great unknown, 'Is Peace Wild?' is German producer, drummer and visual artist Ludwig Wandinger's upcoming release on light-years. He dreamt it up while unpacking the breakdown of a long relationship, working in hotel rooms during the downtime between a series of chaotic live shows. To help empty his mind, Wandinger developed a suite of soulful reflections that prioritize harmony over rhythm and clarity over trivial complexity - music that confronts the eternal duality of romance and tragedy. Almost beatless and consistently sublime, 'Is Peace Wild?' is punctuated by hypnotic lyrical contributions from multi-disciplinary artist, poet and activist Yves B. Golden and producer and vocalist Evita Manji, both of whom bless the album with indispensable friendship and familiarity. "It's almost as if they were telling me a good night story," says Wandinger.

With a series of albums and EPs under his belt already, Wandinger is a tireless solo artist and a prolific collaborator. He's released material for Orange Milk, Gin&Platonic, Creamcake, 3XL, and he worked alongside artists such as Evita Manji, Sara Persico, Grischa Lichtenberger and Brodinski. 'Is Peace Wild?' though emerges as Wandinger’s most personal work to date. The title track opens the album, and Golden's voice breathes softly over Wandinger's warm, lulling arpeggios. "Balloons and birds delight in the flow of air between rooms," she murmurs, floating her surreal phrases in a tranquil pool of pitch-skewed pads and chiming, music box synths. But this airiness doesn't last long: on the noisy, sombre 'Vien', Wandinger interrupts his elegiac, organ-like synths with metallic crashes and distorted, rasping bass, weaving twinkling, pensive notes into the spaces in-between. The oscillation between darkness and light is remarkably even-handed, capturing the aching sense of longing - or "Sehnsucht" - that's at the core of German Romanticism. And it's even more evident on 'Xhausted Form', one of the album's heaviest tracks. Unfolding initially with affecting, sacred chords, the serenity is challenged by eerie, dissonant crunches and unsettling feedback shrieks, yet the spark of romance, in all of its intricacy, never diminishes.

Meanwhile, the album's illusory qualities are fully dilated on 'Fire'. Manji's hypnotic freestyle was recorded in a single take as they were lying in bed on the verge of falling asleep, and provides a quiescent counterpoint to Wandinger's muted trance vibrations. "The world is on fire drowning in its own fluids," they slur into the abyss, vocalizing playfully while Wandinger freezes the sentiment in vanishing 4/4 thuds and dissociated processes. This makes the baroque 'Overlife' and the noisy 'Eternal Image' all the more dynamic. On the latter, Wandinger creates a noisy, apocalyptic atmosphere for Golden's sardonic words, cooling his euphoric synths with hissing white noise and burnished cybernetic textures. "They are afraid of loud noises," Golden mouthes. "Bodies like mine are made for turbulence."

Open-ended and tangled with emotional paradoxes, 'Is Peace Wild?' can be interpreted in many different ways. Wandinger's own serenity is personal, but laying himself bare, he provides listeners with a cracked mirror to consider their unique patchwork of conundrums.

CREDITS

When the world's chatter is hushed to a whisper and emptiness replaces clutter, time falls away completely, exposing a vast, open canvas for the imagination fill with reflection, contemplation and abstraction. On their first collaborative album, released via Caterina Barbieri's light-years label, Grand River and Abul Mogard gaze longingly into the abyss, capturing atemporality, splendour and tranquility with confident, impressionistic sonic strokes. Dynamic and poignant, 'In uno spazio immenso' balances on a knife-edge between booming, operatic grandeur and soft- focus simplicity, casting as much light on the subtle outlines and illusory rhythms as it does its dense, almost overpowering textures.

Berlin-based Dutch-Italian composer and sound designer Aimée Portioli, aka Grand River, has been evolving her unique musical language since she released 'Crescente' on Donato Dozzy and Neel's Spazio Disponibile imprint in 2017. A trained linguist, she uses her instrumentation and advanced processes to challenge cultural perceptions, portraying emotions and moods rather than fixed, visual images. Abul Mogard meanwhile is just one of veteran Italian producer Guido Zen's many aliases, and over a series of acclaimed albums for labels like Ecstatic, Houndstooth and VCO, he's muddled fiction with stark reality, shaking kosmische synth fantasies into post- industrial ambience and blissful shoegaze memories.

Working together, Portioli and Zen find unity in intensity, freezing their discrete concepts and techniques into a glacial emotional expanse. On opening track 'Dissolvi', they peer out hand-in- hand over a colossal, reverberant landscape, conducting booming basses, evaporating voices and brassy synthetic swells that pick out the formidable topography. Beatless but not without rhythm, the composition moves at its own pace, twisting time and form to suggest the duo's obliquely hypnagogic narrative. And with each action, there's inevitably a reaction: 'Frantumi di luce' is a hushed refraction that simmers with intrigue, decorating its subtle, flickering pulse and dazzling rays of thoughtful ambience, while 'Altrove, lontano' transports listeners into a different locale entirely, cloistering its meditative mood with angelic choral echoes and evocative strings.

The album's most devastating track, 'Archi' is an apex of sorts, a collision of widescreen electroid oscillations and overdriven drones that careens into a grinding industrial beat, and 'Sulle barcane' is its serene inverse, a breathy exhalation fashioned from cryptic environmental recordings, static washes and weightless pads. But 'In uno spazio immenso' isn't a story about Portioli and Zen, exactly, it's an invitation to listen to an inner voice that's different for each listener. Space is whatever we want it to be, and how we decide to fill it is a choice that's dependent on the depth of the imagination.

Berlin-based Dutch-Italian composer and sound designer Aimée Portioli, aka Grand River, has been evolving her unique musical language since she released 'Crescente' on Donato Dozzy and Neel's Spazio Disponibile imprint in 2017. A trained linguist, she uses her instrumentation and advanced processes to challenge cultural perceptions, portraying emotions and moods rather than fixed, visual images. Abul Mogard meanwhile is just one of veteran Italian producer Guido Zen's many aliases, and over a series of acclaimed albums for labels like Ecstatic, Houndstooth and VCO, he's muddled fiction with stark reality, shaking kosmische synth fantasies into post- industrial ambience and blissful shoegaze memories.

Working together, Portioli and Zen find unity in intensity, freezing their discrete concepts and techniques into a glacial emotional expanse. On opening track 'Dissolvi', they peer out hand-in- hand over a colossal, reverberant landscape, conducting booming basses, evaporating voices and brassy synthetic swells that pick out the formidable topography. Beatless but not without rhythm, the composition moves at its own pace, twisting time and form to suggest the duo's obliquely hypnagogic narrative. And with each action, there's inevitably a reaction: 'Frantumi di luce' is a hushed refraction that simmers with intrigue, decorating its subtle, flickering pulse and dazzling rays of thoughtful ambience, while 'Altrove, lontano' transports listeners into a different locale entirely, cloistering its meditative mood with angelic choral echoes and evocative strings.

The album's most devastating track, 'Archi' is an apex of sorts, a collision of widescreen electroid oscillations and overdriven drones that careens into a grinding industrial beat, and 'Sulle barcane' is its serene inverse, a breathy exhalation fashioned from cryptic environmental recordings, static washes and weightless pads. But 'In uno spazio immenso' isn't a story about Portioli and Zen, exactly, it's an invitation to listen to an inner voice that's different for each listener. Space is whatever we want it to be, and how we decide to fill it is a choice that's dependent on the depth of the imagination.